The Coming AI Disruption: Lessons from 1899–1929

AI will (hopefully) make the world a better place, but for some people the transition will be brutal.

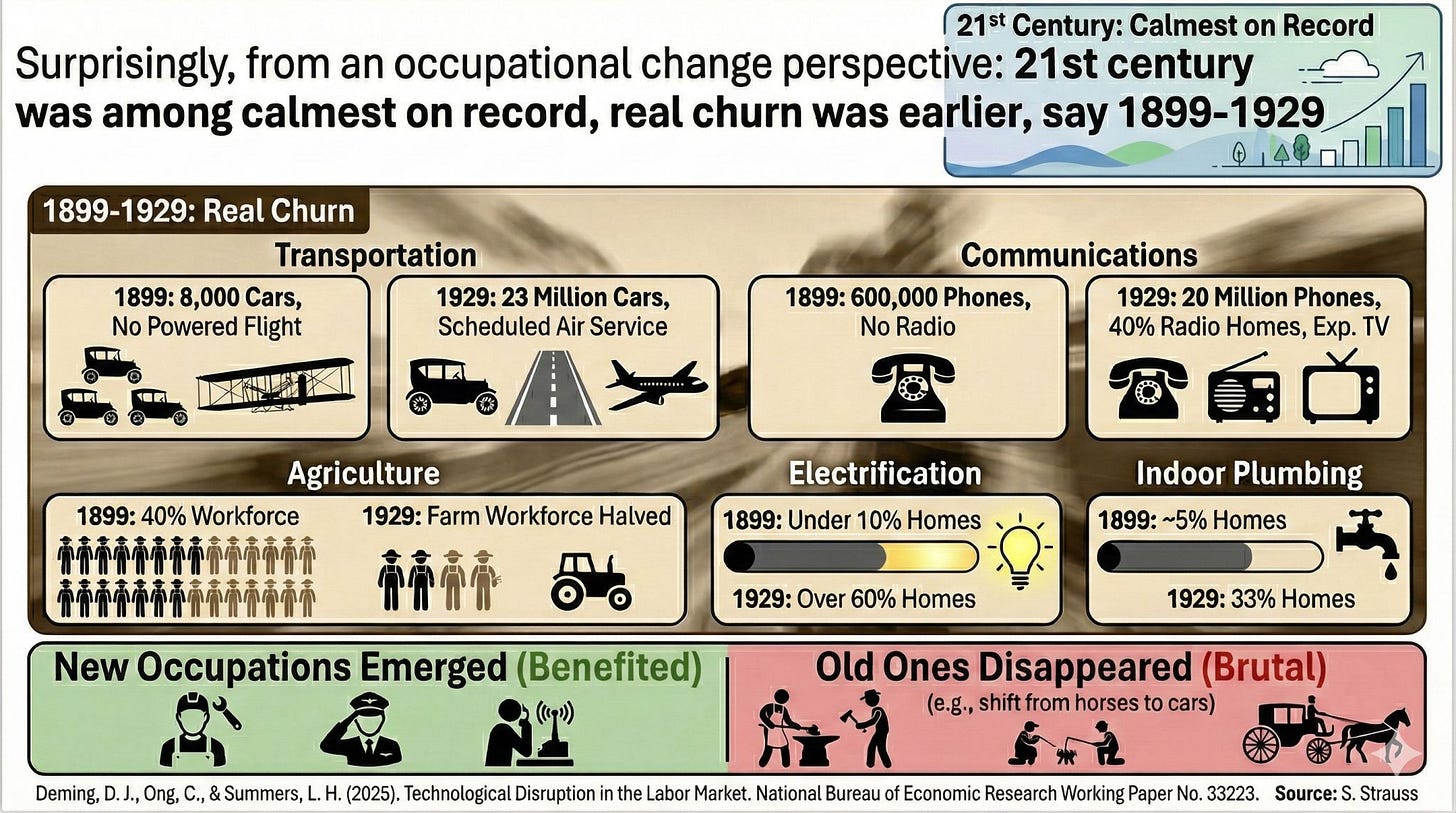

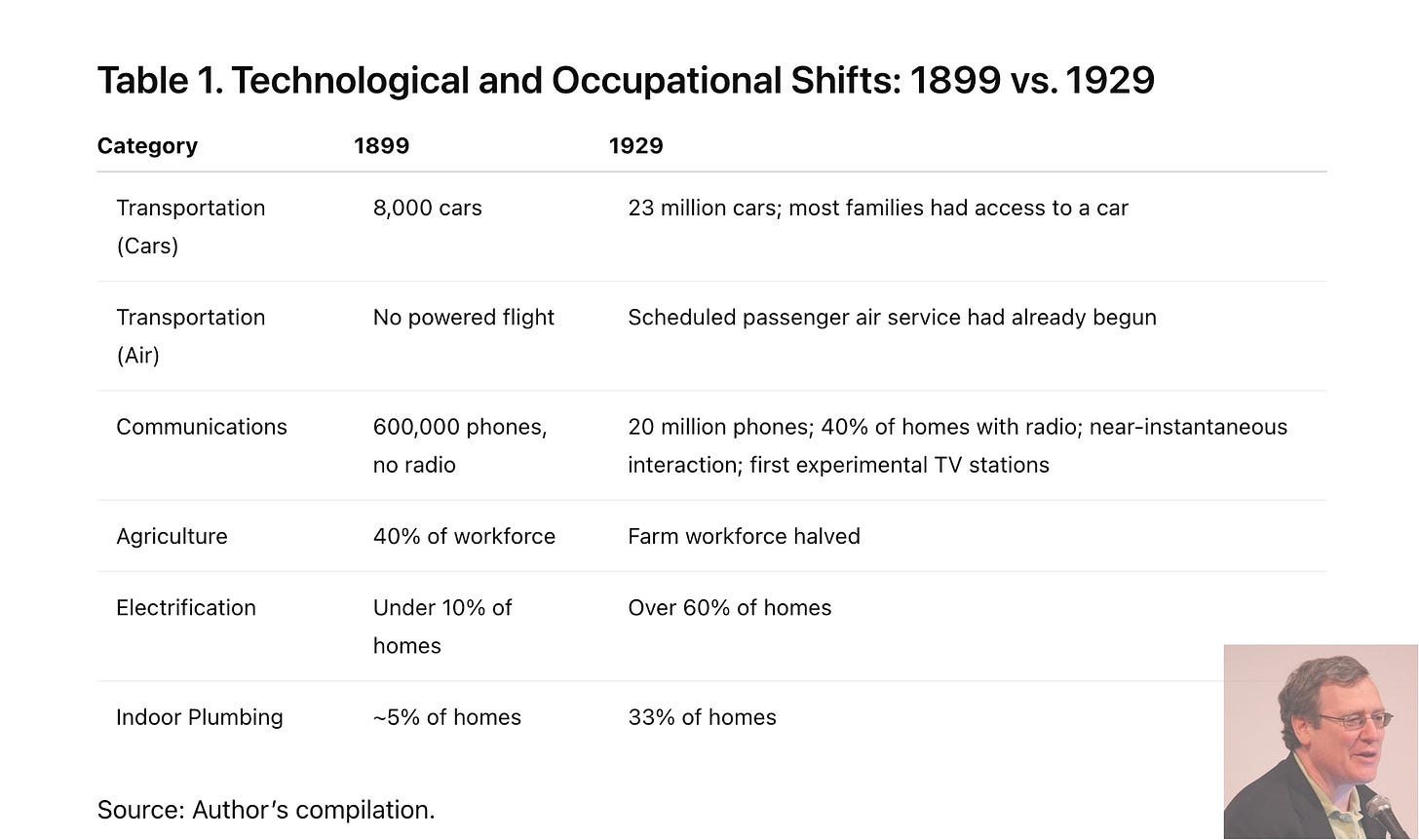

The world of the late 19th century is both unimaginably distant and surprisingly close—all my grandparents were born in the 1880s. Between their teens and middle age, the United States changed from a world where automobiles were curiosities, communications were slow and powered flight seemed impossible, to one of mass car ownership, passenger aviation, and increasingly instantaneous communications (telephones and radio became ubiquitous, and the first TV stations began broadcasting).

It must have felt like magic—and it moved faster than anything we’ve experienced in our lifetimes.

A recent paper published at NBER (Technological Disruption in the Labor Market) looks back at more than a century of data to measure “churn” in the U.S. occupational structure and finds something counterintuitive. Despite the rise of the internet, the China shock to domestic manufacturing, and many other upheavals, 1990–2017 was the least disruptive period they can measure, dating back to 1880. Surprisingly, the first half of the 20th century was among the most disruptive.

Recent change has been evolutionary, which may be why many people are under-estimating the AI revolution that is coming. For purposes of this essay, I am assuming AI will be a “normal technology” (as described by Narayanan and Kapoor), rather than super-intelligence. But that still means change (at the scale being forecast) will damage many incumbent workers—people whose skills are bound up with the old way of doing things—rather than new entrants, who can orient their education and careers toward what’s emerging. Further, and unlike prior technology waves (as noted in a report from the National Academy of Sciences), a consistent result in exposure studies is that AI’s potential task-replication is greater for high-education, high-wage occupations. In short, this technology disruption is coming for higher-end office workers. And if we do achieve artificial general intelligence, the changes will be much more significant and much faster.

The Telephone Operator as Harbinger

A recent paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics (Answering the Call of Automation) illustrates what disruption looked like in that earlier era. By 1920, telephone operators numbered about 400,000—roughly 1% of the non-farm workforce. Then AT&T began replacing them with mechanical switching, city by city, exchange by exchange. After a city converted to dial service, the number of people employed as telephone operators fell immediately by 50 to 80 percent.

For incumbent operators, the impact was lasting: they were less likely to still be working a decade later, and those who did were more likely to have moved into lower-paying jobs. This displacement of existing workers, however, coexisted with job growth in new roles. Task recomposition created novel job categories and career ladders. The technology mattered, but transition policy mattered too—which is worth remembering as we face the transitions triggered by AI.

The Pattern of Transformation

The telephone story is one of many from that era. If the coming AI transition looks more like 1899–1929 than like 1990–2017, it is going to be exhilarating, it will make for a better world, but for some people it will be brutal. Old occupations disappeared and new ones emerged. In 1890, there were roughly 13,800 manufacturers of horse-drawn carriages in the United States; by 1920, fewer than 90 remained. A “teamster” originally drove a team of animals; by 1930, the label remained while the skill set had shifted to driving a truck. The economy expanded over time, but if you were mid-career and your main value was a task the new system no longer needed, the transition was harsh.

A snapshot of the era’s transformation captures how quickly the “impossible” can become ordinary (see Table 1).

Early Signals

We’re already seeing early signals. Using payroll data from ADP, Brynjolfsson, Chandar, and Chen find that early-career workers ages 22–25 in AI-exposed occupations have experienced a 13 percent relative decline in employment since ChatGPT’s release, as companies’ first response to improved productivity has been to reduce new hires. So far, affected early-career workers appear to have found alternative employment, while the number of experienced workers has remained stable or increased. But if past transitions are any guide, deeper disruption may land later—when firms redesign workflows and the technology improves enough to substitute for tasks done by more experienced workers.

How Work Will Reorganize

Over time, organizations will reshape occupations by unbundling tasks, then re-bundling them into new configurations. Entry-level office tasks will be automated first, while many occupations will persist but reorganize around higher-level judgment, orchestration, and accountability. The benefits concentrate where AI complements people—by expanding output and enabling new work. The pain concentrates in high-volume entry-level and administrative work—where AI can directly execute a large share of tasks at good-enough quality.

In a world of ubiquitous AI, roles that supervise, verify, and direct AI will tend to expand, while roles defined by first-pass drafting, basic research, and routine coordination face the greatest risk of contraction.

The biggest shock will not hit people entering the workforce, but office workers with established careers built on tasks that can be unbundled and automated—customer service, credit analysis, marketing copy, contract review. They will be told to re-skill, but re-skilling is far harder mid-career.

People newly entering the workforce will adapt: they will choose different majors, build fluency with new tools, and enter occupations that don’t currently exist. Many will do work that is not AI-proof but AI-native—roles that exist because the tools exist, just as “software developer” couldn’t exist without the computer.

The Limits of Imagination

This difficulty of imagining fundamental change isn’t new. In 1898, urban planners from around the world convened in New York City for the world’s first urban planning conference. One of the major items on the agenda: cities were drowning in horse manure. The planners didn’t consider how rising automobile use would make the issue moot within a generation. They weren’t foolish; they were extrapolating from their recent history. We risk making the same mistake if we merely project today’s world forward — and fail to understand how profoundly AI may reshape the economy.

The deeper lesson from past automation is not that “jobs always come back.” It’s that jobs—if they do come back—come back differently. And the people most likely to be left behind often did everything society asked of them in the old system, only to discover that their hard-won expertise has become yesterday’s technology.

We could treat their redundancy as collateral damage. Or we can try to shape the transition toward broad prosperity.

Selected Bibliography

Brynjolfsson, Erik, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen. 2025. “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence.” Stanford Digital Economy Lab Working Paper (updated November 2025).

Deming, David J., Christopher Ong, and Lawrence H. Summers. 2025. “Technological Disruption in the Labor Market.” NBER Working Paper No. 33323 (January 2025).

Erickson, Amanda. 2012. “A Brief History of the Birth of Urban Planning.” Bloomberg CityLab, August 24, 2012. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-08-24/a-brief-history-of-the-birth-of-urban-planning.

Feigenbaum, James, and Daniel P. Gross. 2024. “Answering the Call of Automation: How the Labor Market Adjusted to Mechanizing Telephone Operation.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 139, no. 3: 1879–1939. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjae019.

Handa, Kunal, Alex Tamkin, Miles McCain, Saffron Huang, Esin Durmus, Sarah Heck, Jared Mueller, Jerry Hong, Stuart Ritchie, Tim Belonax, Kevin K. Troy, Dario Amodei, Jared Kaplan, Jack Clark, and Deep Ganguli. 2025. “Which Economic Tasks Are Performed with AI? Evidence from Millions of Claude Conversations.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.04761. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.04761.

Ide, Enrique. 2025. “Automation, AI, and the Intergenerational Transmission of Knowledge.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.16078v3 (August 19, 2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.16078.

Marguerit, David. 2025. Augmenting or Automating Labor? The Effect of AI Development on New Work, Employment, and Wages. LISER, March 2025.

Narayanan, Arvind, and Sayash Kapoor. 2025. “AI as Normal Technology: An Alternative to the Vision of AI as a Potential Superintelligence.” Knight First Amendment Institute, April 15, 2025.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2024. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27644.

Nuzzo, Andrea, Andreas Kremer, Asin Tavakoli, Holger Harreis, Sebastian Schneider, and Stephan Beitz. 2025. “The Future Is Agentic: AI’s Role in the End-to-End Corporate Credit Process.” McKinsey & Company (Risk & Resilience), December 12, 2025.

Raman, Aneesh. 2025. “A.I. Is Coming for Entry-Level Jobs.” The New York Times (Guest Essay), May 19, 2025.

Sigelman, Matt. 2025. “How the Internet Rewired Work—and What That Tells Us About AI’s Likely Impact.” The Wall Street Journal, November 22, 2025.